© bOURNE uNIVERSITY 2021

AZERBAIJAN-ARCHAEOLOGISTS DISCOVER MORE

ANCIENT RUINS OF AN EEMIAN CASPIAN

CIVILIZATION

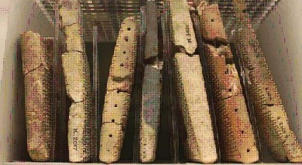

Baku l A team of archaeologists working with the Ganga Academy of Sciences, investigating preservations on a petroglyph engraving site near the Gobustan Rock Art Cultural Landscape, have discovered the ruins of several large stone silo structures dating back to the Palaeolithic. The vast remains of stone ground grains indicates the site was a great agricultural center that could have sustained an ancient Caspian civilization, remaining unknown to archaeology until now. The scientists were utilizing ground penetrating radar from the NASA launched SIR-A satellite imaging system when their survey images revealed the buried foundations of ancient buildings near Qobustan. In August 2017, the team of archaeologists from Ganga Academy of Sciences were called to the site to launch an initial investigation of the discovery. They quickly identified the ruins as a major prehistoric grain storage center. Several weeks of computer data analysis have uncovered evidence of a large number of structures of what appears to be temple mounds, royal palaces, grain silos, irrigation canals, residential communities, and large administration centers. The building materials, architecture and relics unearthed near the Qobustan site have proven comparable to the ruins found in the river system region of the Tigris–Euphrates Mesopotamia and the Nile's Egypt. "There is mounting evidence that this was a great granary city," states Professor Hassan Isakhanli of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, "that was built to distribute regional commercial trade. These people were without doubt pre-Indo-European people. The recent carbon dating analysis has concluded the ruin has dated from around 100,000 BP, and could have been the influential throughout the ancient Caspian Basin. We have determined the buildings and relics on this site have been consistent with recently discovered Corean cities and Corean temples." The excavations have uncovered the remains of four massive grain silos, which archaeologists estimate stood nearly two hundred feet high. The city appears to have been built as a fortress, with high walls, defense towers and with warriors who were buried with their weapons, armor and remains of horses and chariots. During their investigation of the site, the archaeologists have unearthed a large variety and diverse number of skeletons. The majority have been reported as males, dozens of females and nearly the same number of children. Some of the adults had fallen in the streets and perished having been suddenly overcome, or hiding in the stairwells with their belongings and arms. Other remains were found buried in mounds of hardened ash in their sudden death throes and preserved until now by whatever calamity abruptly overcame them. Several iron pots and tools were found near the remains, such as knives, swords, shields and also large pieces of armor. Many artifacts discovered suggest the Coreans had then reached a technological level comparable to the Mesopotamian civilizations during the Middle Bronze Age, as numerous idols and coins were discovered at the site. Many remains of various homini, such as homo erectus, ergaster, Neanderthal and primates measuring nine feet tall have been found in the ruins, suggesting the city conducted commerce with these indigenous peoples. The various remains of figs from the Middle East and Asia were found in the pottery of one their merchants, and copper, molybdenum, salt and sulphur from Armenia and Turkmenistan were found in the smelters of one of their tradesman. The evidence suggests that the Coreans had wide networks of trade routes throughout the Caspian Basin, and could have explored as far as Northern Iran at the time. Large pots well preserved from the excavation. Remains of figs, fruits and grains from throughout the Middle East and Western Asia were found among the ancient houses. It is widely believed that the crossing of genetic grasses into "bread wheats" occurred during the Stone Age in the Middle East before the appearance of the ancient Sumerians in the Fertile Crescent. Professor Hassan Isakhanli believes that the Coreans could have built this city as an agricultural currency center, the abundance of grain becoming the Coreans' core commercial banking and prosperous urban communities. It was very remote from the largest Corean cities, ports and fortresses, which marvels how the Corean civilization traded widely across the Caspian Basin. "The most enticing map comes from the British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard's Nurubi Fragments found in 1852 which accurately mapped the geography of the Caspian Sea region some 130 centuries ago," says Professor Isakhanli. "When we discover the Coreans' agricultural capability, their grain routes had reached as far as Eastern Turkey and the Armenian Plain using their large scale road systems, connecting the many Corean cities and nations throughout the grain cities. We can only imagine the amazing engineering feats these people mastered when they reached the height of Corean civilization!" The Coreans were an ancient pre-Sumerian culture that flourished and migrated from their Comorian (present day Armenia) communities throughout large regions of the western and northern Caspian Sea Basin, reaching as far as Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan, who appeared shortly after the Riss Glaciation in 130,000 BP. Inventing an advanced urban civilization with a common language and writing, they are thought to have created science, arts, astronomy and religions that dominated their western Caspian regions before their demise. Remnants of them migrated to the ancient floodplain along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers thousands of years later to ancient Mesopotamia. The first suspected grain city was excavated in 2012, near Shirvan, located between Alat and Salyan on the Shirvan Plain. The remains of bread wheats found in the silos have proven that southern cities shipped grains northwards since these strains are not native to eastern Azerbaijan. The archaeologists believe that the Corean ruins were recently discovered since global warming melted the Scandinavian Ice Sheet around 16,000 BP, resulting in massive rivers that flooded the northwest coastline of the Caspian Sea region. The Sea of Azov rose over 160 feet (50 meters) overflowing into the Caspian Sea, and flooded the Kuma-Manych Depression into the Black Sea. Near the end of the Pleistocene this would have moved great mountains of water throughout the former Corean regions from the eastern Caucasus Mountains to Eastern Turkey and Northern Iran, burying their cities under hundreds of feet of mud and debris. Only the use of ground penetrating radar has revealed these ancient, mysterious ruins to the modern world.

THE BOURNE JOURNAL OF

ARCHAEOLOGY

CURRENT ISSUE

Member Since May 1922

Explore

Discover

Find

Catalog

Publish

Reward

LONDON-ROME-BERLIN-MOSCOW-NAPLES

Recent Articles

Proud Sponsor of Bourne’s Journal

Sponsored Works

News of the World

related posts

SHARE ON:

SHARE ON:

© bOURNE uNIVERSITY 2021

AZERBAIJAN-ARCHAEOLOGISTS DISCOVER

MORE ANCIENT RUINS OF AN EEMIAN CASPIAN

CIVILIZATION

Baku l A team of archaeologists working with the Ganga Academy of Sciences, investigating preservations on a petroglyph engraving site near the Gobustan Rock Art Cultural Landscape, have discovered the ruins of several large stone silo structures dating back to the Palaeolithic. The vast remains of stone ground grains indicates the site was a great agricultural center that could have sustained an ancient Caspian civilization, remaining unknown to archaeology until now. The scientists were utilizing ground penetrating radar from the NASA launched SIR-A satellite imaging system when their survey images revealed the buried foundations of ancient buildings near Qobustan. In August 2017, the team of archaeologists from Ganga Academy of Sciences were called to the site to launch an initial investigation of the discovery. They quickly identified the ruins as a major prehistoric grain storage center. Several weeks of computer data analysis have uncovered evidence of a large number of structures of what appears to be temple mounds, royal palaces, grain silos, irrigation canals, residential communities, and large administration centers. The building materials, architecture and relics unearthed near the Qobustan site have proven comparable to the ruins found in the river system region of the Tigris–Euphrates Mesopotamia and the Nile's Egypt. "There is mounting evidence that this was a great granary city," states Professor Hassan Isakhanli of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, "that was built to distribute regional commercial trade. These people were without doubt pre-Indo-European people. The recent carbon dating analysis has concluded the ruin has dated from around 100,000 BP, and could have been the influential throughout the ancient Caspian Basin. We have determined the buildings and relics on this site have been consistent with recently discovered Corean cities and Corean temples." The excavations have uncovered the remains of four massive grain silos, which archaeologists estimate stood nearly two hundred feet high. The city appears to have been built as a fortress, with high walls, defense towers and with warriors who were buried with their weapons, armor and remains of horses and chariots. During their investigation of the site, the archaeologists have unearthed a large variety and diverse number of skeletons. The majority have been reported as males, dozens of females and nearly the same number of children. Some of the adults had fallen in the streets and perished having been suddenly overcome, or hiding in the stairwells with their belongings and arms. Other remains were found buried in mounds of hardened ash in their sudden death throes and preserved until now by whatever calamity abruptly overcame them. Several iron pots and tools were found near the remains, such as knives, swords, shields and also large pieces of armor. Many artifacts discovered suggest the Coreans had then reached a technological level comparable to the Mesopotamian civilizations during the Middle Bronze Age, as numerous idols and coins were discovered at the site. Many remains of various homini, such as homo erectus, ergaster, Neanderthal and primates measuring nine feet tall have been found in the ruins, suggesting the city conducted commerce with these indigenous peoples. The various remains of figs from the Middle East and Asia were found in the pottery of one their merchants, and copper, molybdenum, salt and sulphur from Armenia and Turkmenistan were found in the smelters of one of their tradesman. The evidence suggests that the Coreans had wide networks of trade routes throughout the Caspian Basin, and could have explored as far as Northern Iran at the time. Large pots well preserved from the excavation. Remains of figs, fruits and grains from throughout the Middle East and Western Asia were found among the ancient houses. It is widely believed that the crossing of genetic grasses into "bread wheats" occurred during the Stone Age in the Middle East before the appearance of the ancient Sumerians in the Fertile Crescent. Professor Hassan Isakhanli believes that the Coreans could have built this city as an agricultural currency center, the abundance of grain becoming the Coreans' core commercial banking and prosperous urban communities. It was very remote from the largest Corean cities, ports and fortresses, which marvels how the Corean civilization traded widely across the Caspian Basin. "The most enticing map comes from the British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard's Nurubi Fragments found in 1852 which accurately mapped the geography of the Caspian Sea region some 130 centuries ago," says Professor Isakhanli. "When we discover the Coreans' agricultural capability, their grain routes had reached as far as Eastern Turkey and the Armenian Plain using their large scale road systems, connecting the many Corean cities and nations throughout the grain cities. We can only imagine the amazing engineering feats these people mastered when they reached the height of Corean civilization!" The Coreans were an ancient pre-Sumerian culture that flourished and migrated from their Comorian (present day Armenia) communities throughout large regions of the western and northern Caspian Sea Basin, reaching as far as Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan, who appeared shortly after the Riss Glaciation in 130,000 BP. Inventing an advanced urban civilization with a common language and writing, they are thought to have created science, arts, astronomy and religions that dominated their western Caspian regions before their demise. Remnants of them migrated to the ancient floodplain along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers thousands of years later to ancient Mesopotamia. The first suspected grain city was excavated in 2012, near Shirvan, located between Alat and Salyan on the Shirvan Plain. The remains of bread wheats found in the silos have proven that southern cities shipped grains northwards since these strains are not native to eastern Azerbaijan. The archaeologists believe that the Corean ruins were recently discovered since global warming melted the Scandinavian Ice Sheet around 16,000 BP, resulting in massive rivers that flooded the northwest coastline of the Caspian Sea region. The Sea of Azov rose over 160 feet (50 meters) overflowing into the Caspian Sea, and flooded the Kuma-Manych Depression into the Black Sea. Near the end of the Pleistocene this would have moved great mountains of water throughout the former Corean regions from the eastern Caucasus Mountains to Eastern Turkey and Northern Iran, burying their cities under hundreds of feet of mud and debris. Only the use of ground penetrating radar has revealed these ancient, mysterious ruins to the modern world.

THE BOURNE JOURNAL OF

ARCHAEOLOGY

related posts

SHARE ON:

Recent Articles

Sponsored Works

Proud Sponsor of Bourne’s Journal

SHARE ON:

© bOURNE uNIVERSITY 2021

AZERBAIJAN-

ARCHAEOLOGISTS DISCOVER

MORE ANCIENT RUINS OF AN

EEMIAN CASPIAN

CIVILIZATION

Baku l A team of archaeologists working with the Ganga Academy of Sciences, investigating preservations on a petroglyph engraving site near the Gobustan Rock Art Cultural Landscape, have discovered the ruins of several large stone silo structures dating back to the Palaeolithic. The vast remains of stone ground grains indicates the site was a great agricultural center that could have sustained an ancient Caspian civilization, remaining unknown to archaeology until now. The scientists were utilizing ground penetrating radar from the NASA launched SIR-A satellite imaging system when their survey images revealed the buried foundations of ancient buildings near Qobustan. In August 2017, the team of archaeologists from Ganga Academy of Sciences were called to the site to launch an initial investigation of the discovery. They quickly identified the ruins as a major prehistoric grain storage center. Several weeks of computer data analysis have uncovered evidence of a large number of structures of what appears to be temple mounds, royal palaces, grain silos, irrigation canals, residential communities, and large administration centers. The building materials, architecture and relics unearthed near the Qobustan site have proven comparable to the ruins found in the river system region of the Tigris–Euphrates Mesopotamia and the Nile's Egypt. "There is mounting evidence that this was a great granary city," states Professor Hassan Isakhanli of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, "that was built to distribute regional commercial trade. These people were without doubt pre-Indo-European people. The recent carbon dating analysis has concluded the ruin has dated from around 100,000 BP, and could have been the influential throughout the ancient Caspian Basin. We have determined the buildings and relics on this site have been consistent with recently discovered Corean cities and Corean temples." The excavations have uncovered the remains of four massive grain silos, which archaeologists estimate stood nearly two hundred feet high. The city appears to have been built as a fortress, with high walls, defense towers and with warriors who were buried with their weapons, armor and remains of horses and chariots. During their investigation of the site, the archaeologists have unearthed a large variety and diverse number of skeletons. The majority have been reported as males, dozens of females and nearly the same number of children. Some of the adults had fallen in the streets and perished having been suddenly overcome, or hiding in the stairwells with their belongings and arms. Other remains were found buried in mounds of hardened ash in their sudden death throes and preserved until now by whatever calamity abruptly overcame them. Several iron pots and tools were found near the remains, such as knives, swords, shields and also large pieces of armor. Many artifacts discovered suggest the Coreans had then reached a technological level comparable to the Mesopotamian civilizations during the Middle Bronze Age, as numerous idols and coins were discovered at the site. Many remains of various homini, such as homo erectus, ergaster, Neanderthal and primates measuring nine feet tall have been found in the ruins, suggesting the city conducted commerce with these indigenous peoples. The various remains of figs from the Middle East and Asia were found in the pottery of one their merchants, and copper, molybdenum, salt and sulphur from Armenia and Turkmenistan were found in the smelters of one of their tradesman. The evidence suggests that the Coreans had wide networks of trade routes throughout the Caspian Basin, and could have explored as far as Northern Iran at the time. Large pots well preserved from the excavation. Remains of figs, fruits and grains from throughout the Middle East and Western Asia were found among the ancient houses. It is widely believed that the crossing of genetic grasses into "bread wheats" occurred during the Stone Age in the Middle East before the appearance of the ancient Sumerians in the Fertile Crescent. Professor Hassan Isakhanli believes that the Coreans could have built this city as an agricultural currency center, the abundance of grain becoming the Coreans' core commercial banking and prosperous urban communities. It was very remote from the largest Corean cities, ports and fortresses, which marvels how the Corean civilization traded widely across the Caspian Basin. "The most enticing map comes from the British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard's Nurubi Fragments found in 1852 which accurately mapped the geography of the Caspian Sea region some 130 centuries ago," says Professor Isakhanli. "When we discover the Coreans' agricultural capability, their grain routes had reached as far as Eastern Turkey and the Armenian Plain using their large scale road systems, connecting the many Corean cities and nations throughout the grain cities. We can only imagine the amazing engineering feats these people mastered when they reached the height of Corean civilization!" The Coreans were an ancient pre-Sumerian culture that flourished and migrated from their Comorian (present day Armenia) communities throughout large regions of the western and northern Caspian Sea Basin, reaching as far as Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan, who appeared shortly after the Riss Glaciation in 130,000 BP. Inventing an advanced urban civilization with a common language and writing, they are thought to have created science, arts, astronomy and religions that dominated their western Caspian regions before their demise. Remnants of them migrated to the ancient floodplain along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers thousands of years later to ancient Mesopotamia. The first suspected grain city was excavated in 2012, near Shirvan, located between Alat and Salyan on the Shirvan Plain. The remains of bread wheats found in the silos have proven that southern cities shipped grains northwards since these strains are not native to eastern Azerbaijan. The archaeologists believe that the Corean ruins were recently discovered since global warming melted the Scandinavian Ice Sheet around 16,000 BP, resulting in massive rivers that flooded the northwest coastline of the Caspian Sea region. The Sea of Azov rose over 160 feet (50 meters) overflowing into the Caspian Sea, and flooded the Kuma-Manych Depression into the Black Sea. Near the end of the Pleistocene this would have moved great mountains of water throughout the former Corean regions from the eastern Caucasus Mountains to Eastern Turkey and Northern Iran, burying their cities under hundreds of feet of mud and debris. Only the use of ground penetrating radar has revealed these ancient, mysterious ruins to the modern world.

THE BOURNE JOURNAL OF

ARCHAEOLOGY

SHARE ON:

SHARE ON:

Member Since May 1922

Explore

Discover

Find

Catalog

Publish

Reward

LONDON-ROME-BERLIN-MOSCOW-NAPLES

Proud Sponsor of Bourne’s Journal

Like our Sponser